The final part of this three-part feature will focus on the largest, most important group that, indeed, makes it all tick; the ‘active’ fans that thrive on ‘being there.’ The fans who drive their side forward, the fans whose hopes and dreams rest upon the shoulders of eleven lone players, the fans whose lives revolve around getting to the beautiful game. But this rich experience has largely gone. In the EFL, for example, thousands of fans are banished to Ifollow, the dubious, amateurish £10 computer stream, complete with nail-biting delays and questionable camera work. Every game played in front of vast swathes of empty plastic seats, punctuated by the odd cardboard cut-out, serves as a stark reminder of the impact that COVID-19 is having on so many lives. Loyal supporters, now confined to the comfort of their homes, are tasting the sterile world of ‘armchair,’ Sky Sports lovers, who embrace the action from afar. In essence, the qualities of being a ‘proper fan’ may require the ‘live’ experience. Be part of it. ‘Watch it, drink it in,’ as Martin Tyler would say.

Football – more than ‘just a game’?

‘Football is not just a matter of life or death. It’s much more important than that”. This much-repeated quote from the late Bill Shankly is, arguably, a bit extreme, but its intent is useful to make the point that there’s a bit more to football than may meet the eye.

Aside from being unable to watch a match ‘in the flesh,’ fans may have missed many other vital aspects entwined in a typical matchday experience. For thousands of fans, football forms, literally, a ‘part’ of their lives. Waking on a Saturday morning to the prospect of meeting mates, the journey to the ground, the team sheet, a few beers, a burger, the anticipation, the songs, the emotion, the joy, the ….despair. Supporting their team is what may propel them through the working week. The hope that Saturday brings may countenance the often harsh reality of life. So there is always an eye on the weekend; it’s a supporters release, a day to forget everything else and focus on the football.

Embed from Getty ImagesAn in-depth interview, carried out in the serene surroundings of The Petersfield Bookshop, situated in the depths of Hampshire countryside, serves to give some insight into what Covid World may have taken from fans. In stark contrast to a matchday stadium, this location is home and workplace of John Portsmouth Fc Westwood, arguably, one of the most famous fans in the world. His ‘infamous’ bell and tuneless chanting can even be heard on Fifa: “The weekend gives you something to look forward to; it’s a release; I don’t drink during the week and then enjoy myself on a Saturday, football gives you something to focus on, and it’s been taken from my life this season,” said Westwood. [i]

He feels the release football offers for fans is crucial: “I work in a quiet antiquarian bookshop in Petersfield, going from there to how I am on a Saturday are two completely different worlds.”

He added: “Getting into grounds, cheering, singing songs, feeling the roar and smelling the crowd, the things we collectively do, we have taken that for granted. I’ve been stabbed, bottled, punched, and kicked, but going through that to support your team with your mates; it’s a buzz a feeling you cannot replicate.”

“I haven’t seen some of my best mates for a year. The social side of football is so important as you get older, and it’s completely gone this season, and I need it back. The excitement of the game, beers, songs, pool it’s what football is all about.”

JOHN PORTSMOUTH FOOTBALL CLUB WESTWOOD

Despite current restrictions, Westwood has, remarkably, followed Pompey to every game this season. He has driven his battered minibus the length and breadth of the U.K. to stand outside grounds giving support and, of course, ring his bell. In many ways, he epitomises the importance of attending live games, despite taking things to the extreme!

To further highlight Westwood’s point regarding the importance of a match day, research by I. Jones into Luton Town fans found that the level of fan identification is linked to the relationship between them and the club. If the club is struggling or not performing at a high level, fans were less likely to identify with the club in everyday life. Supporting a club almost dictates people’s lives; it makes them happy, it ruins their day, it’s a feeling shared by many people. The process of going to football with like-minded people can be seen to shape one’s thought processes in a particular way. Like-minded people all attending for roughly the same reasons. It could shape people; it may have an impact on their overall interpretations of life. [ii]

Embed from Getty ImagesA wide variety of people engage in fandom, with, crucially, a wide-ranging level of opinions. Despite these differences, the sheer ‘emotional experience’ of attending a match may mask (or smooths) any potential societal differences. For example, Cleland and Doidge’s research highlights the atmosphere as a ‘collective experience’ that links many people under shared experiences of singing, clapping, and cheering in unison. Conversations that take place at the football about football develop friendships that are advanced through regular discussions in and around the game. Perhaps the most significant point here is that a ‘collective experience reduces race, colour, social differences, etc.; it becomes about being a part of ‘identifying’ with a group. A ‘football’ group.[iii]

Adding to this idea, Emile Durkheim, cited in ‘Collective action and football fandom,’ suggests society is powerful when individuals are connected to others. Supporters attending a match, enjoying the atmosphere, engaging in conversation, and developing friendships could all be seen to enhance this form of self-worth and power. So, it could be argued that the continued absence of fans in stadia has temporarily removed this aspect from their lives. They cannot express emotions like they usually would, and engaging in friendships cannot occur as effortlessly. Not being able to express feelings and meet friends could potentially lead to difficulties in everyday life. Frustration, loneliness, and depression, for example, have been regularly cited in the media as yet another negative consequence of Covid.

How missing live football may influence identity

To understand how aspects of a fan’s actual ‘identity can be negatively influenced (by missing ‘live’ football), it may be possible to use ‘Identity Process Theory, first theorised by Glynis Breakwell. This particular model suggests that identity can be broadly categorised into four components; distinctiveness, self-efficacy, continuity, and self-esteem. Being a football fan provides an element of ‘distinctiveness’ as you support your unique club. With unique ‘club colours, players, songs and characters,’ an ‘away’ fan, visiting a distant city, fans can certainly stand out. ‘Self-efficacy’ relates to being ‘good at something. Sing-ing, cheering, and being the loudest and most choreographed are all elements that make fans feel good at something and better at it than other fans. Moving on, the continuous pilgrimage of football fans provides a sense of ‘continuity’ in their lives, going to matches home and away every week, for example. Finally, ‘self-esteem’ is, in part, fuelled by being associated with a successful result and being a part of a like-minded group. Sadly, this season has seen all of these elements be dramatically affected as they cannot be undertaken. [iv]

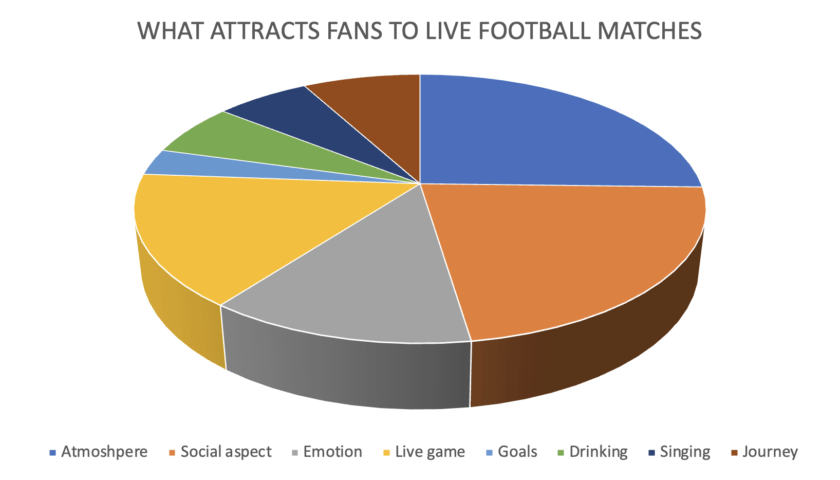

To try and link the four premises of Identity Process Theory to what fans report to have missed most, a questionnaire was sent to football fans using the popular Po4CAST fans site on Twitter. Fans were asked to list three things they missed the most and to rank in order. A total of 68 responses provided the following categories and percentages:[v]

From the graph, the four main things that fans missed were 1. Atmosphere 2. Social 3. Live game (attending) and 4. Emotion. This small survey allowed for fans to generate these rather broad categories. However, they can be linked to Identity Process Theory as a means of showing that not attending matches may harm an individual’s identity.’ Using the IPT Model, ‘Distinctiveness’ would draw heavily on visiting a club’s unique environment, maybe sporting unique club colours. It is linked with both atmosphere (1) and Live Game (3). Self-efficacy could be satisfied with meeting up with friends, Social (2) and having a good sing – song and goal celebration Live game (3) and emotion (4). Continuity is covered easily with all four categories: all ‘regular’ football experiences that fans crave and are now missed. The final aspect of IPT is self-esteem, feeling good about oneself. Again, the four main fan responses, showing what they have missed the most, incorporate this with Social (2), being with mates, and emotion (4), cheering a winning goal for ‘your’ team! The limited data from this small survey has been evaluated using the key components of Identity Process Theory to show that some key items that ‘active’ fans are missing may be related to identity issues. Being a ‘fan’ involves, clearly, more than just watching the game: it’s so much more.

Conclusion

To summarise, unlike the previous debates on the effects of empty stadiums on players and referees, the impression empty stadia has left on fans is there for all to see; it’s clear-cut. There are no variables to suggest other aspects of life in lockdown have made up for the emotional cataclysm that empty stadia has caused. John’ Portsmouth Fc’ Westwood has shed some light on the significance of going to ‘the footy’; it’s more than just to watch the match. The Luton Town fans research, I. Jones, mentions the importance of ‘identification between fans and their club. Cleland and Doidge highlighted ‘match atmosphere’ as a ‘collective experience,’ and Durkheim adds to this research with the theme of fans being ‘connected.’

Continuing this theme, being an ‘active’ fan involves far more than simply attending a live game; travel, singing, meeting friends, celebrating, wearing team colours, etc., become a part of a fans’ identity. It is the impact upon identity that is the crucial talking point in this investigation. Identity Process Theory, suggests continuity, self-esteem, distinctiveness, and self-efficacy are crucial building blocks of identity. Using this model and some survey data from 68 ‘fans,’ it is shown that attending live matches may provide much to link with a persons’ identity.

Of course, further’ post-Covid’ research that follows this ‘identity theme could include a more significant sample plus a selection of questions that are more directly targeted towards the four aspects of Identity Process Theory.

Once the crowds return, there may be a wealth of data to more accurately assess the true impact of Covid upon the ‘fans,’ arguably the key players in the game.

[i] Interview with John ‘Portsmouth football club’ West (socially distanced) 15/04/2021. 07979526057

[ii] Jones, I., 1998. Football Fandom: football fan identity and identification at Luton Town football club. [Online]

Available at: https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.436450

[Accessed 10 03 2021].

[iii] Jamie Cleland, M. D. P. M. P. W., 2018. Collective action and football fandom: A relational sociological approach.. s.l.:Spring international publishing AG.

[iv] Breakwell, G. M 1984 Identity process theory: Identity, social action and social change, Cambridge University Press 2014.

[v] Survey found here